I stumbled upon a word document that I saved from a 2012 road trip report to KY. My have times changed.

Kentucky Bourbon Trip

Last week, Randy Blank & I left Houston on Tuesday morning for our road trip to KY. We stopped Tuesday night in Memphis and we ate some above average BBQ at Cozy Corner (had been on Food Network’s D.D.D.) and drank some good beer at the Flying Saucer. The next day on our way to Bardstown, KY, we toured the Corvette Museum in Bowling Green, KY. The factory where GM makes all Corvettes is right next door.

We arrived in Bardstown and had a group dinner that night at local restaurant with Wes Henderson from Angel’s Envy Bourbon. Wes spoke to our group about his family’s involvement in the Bourbon industry and their decision to launch this product. While this a “sourced” bourbon that is then aged in Port barrels, they do have plans to start their own craft distillery. Wes did say this was produced for them to their mashbill specifications. They plan to introduce a cask strength version of Angel’s Envy by the end of this year. This will be aged much longer in port barrels; up to 2 years vs. 6 months. Wes brought samples of this cask strength as well as standard Angel’s Envy for us to try. I have to say while I’m not in love with this bourbon, I do love the passion Wes has for the product their family is making. If you ever get the chance to meet Wes, be sure to ask him why he is not allowed in Canada (story involves a road crew and the band INXS).

The group I’m involved with has about 70 members and about half made this trip to KY. After dinner, we had a conference room reserved at our hotel and everybody brought a bottle or 2. It was a great selection of bourbon to select from.

On Thursday, Randy & I got up early and went to friend’s house, Doug, who lives in KY out in the boonies. I think his neighbors next door might be moonshiners. We smoked 3 briskets that made the trip up with us from Texas. One member of our group works as a chef and cooked a bacon wrapped stuffed pork loin that was out this world. I’ve attached a picture – pure food porn. While we were cooking at Doug’s, most of our group went to Four Roses for barrel selection and lunch. Four Roses is at the top of my list and the group agrees, we selected 3 barrels for purchase. These barrels were recipe OBSF, OESK, and OESF – all will be bottled at proof and unfiltered. Doug has been collecting whiskey, both Bourbon and Scotch, for a very long time. He recently finished out his basement and built shelving to display his collection. It’s over 2500 bottles and I bowed down to this like I was at the altar. I have a picture of it on my phone I can show you, but Doug asked for photos not to be posted to internet.

On Friday morning, we visited Buffalo Trace to select barrels of Old Weller Antique (OWA). They rolled out 12 barrels for us to pick from. They were all the same age and all stored in same warehouse location. One might think they would all taste the same, but you would be very wrong. I brought with me a sample of off the shelf OWA. I used this as baseline to compare. After tasting the first 6 samples, I was disappointed and did not find anything I thought was better than the normal OWA. However, started with barrel 7, I knew we had some winners. On barrel 9, Randy looked at me and said If this barrel does not get selected, it’s going home with me. The group purchased barrels 7, 8, and 9 and a subgroup purchased 2 additional barrels.

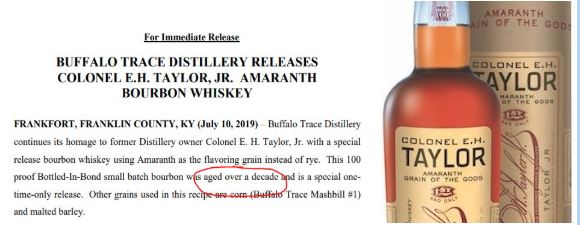

After the tasting, we received a behind the scene tour. I’ve toured Buffalo Trace many times and was pleasantly surprised that we toured areas I had not seen. This included the barrel fill and barrel dump area. Attached is a picture of me at Buffalo Trace collecting some barrel char on the dump line. These char pieces fall out of barrel and are great to use on your grill or smoker. FYI – I learned to always take a glass with on tours. Also, on this line, I filled my glass directly out of the barrel with some Ancient Ancient Age – very tasty. Later we walked through a lab area where they were preparing for the next release in Old Taylor series. This will be a barrel proof, about 134 proof, bourbon and should hit your retailer in 3-4 months. A Buffalo Trace employee had a 200ml sample bottle he was passing around for us to nose. Again – my glass came in handy!

From Buffalo Trace, we made our way to Independent Stave Company. They make the barrels for several distillers. I’ve traveled back to KY many times over the years without seeing this. It is a very interesting process and while there is some automation, barrel assemble is still an art. The cooper hand picks the staves required for the barrels. Different distilleries specify how many staves per barrel, so the cooper must select the right size staves to complete barrel to the specifications.

From Independent Stave, we made our way back to Doug’s for some porch sitting and sipping bourbon. Bob and Allen Richards had arrived in KY that morning and they caught up with us at Doug’s. Doug has an amazing single malt collection that were open for anybody to sample, so Bob and Allan were both in heaven. From Doug’s we left to go to the Gazebo. Bardstown has a Best Western hotel called the General Nelson (GN). The GN has an outdoor Gazebo that starting in 2001 became a default gathering place for forum members of StraightBourbon.com. I made my first trip to GN in 2003 and have been a regular at the Gazebo table since. Hundreds of folks show up that I might see only once a year but through the years have become good friends. Hard to put in words, but suffice to say, I think it is something special.

The next morning, we visited Drew Kulsveen and KY Bourbon Distillers (KBD). I can say that tomorrow has finally arrived – KBD is now distilling. It took many years, but KBD is now filling 16 full size barrels a day. They are still working on some pump issues and plan to ramp up to 50 barrels a day. Alas, this will not be ready for sale for many years. Our group was there to taste other barrels that KBD owns. Our group had previously purchased barrels from this specific source when it was 7 years old, then again at 8 and now 9 years old. We tasted from 6 barrels and selected 2 for purchase. Honey, maple, brown sugar, cherries – a great bourbon that we will have bottled at barrel proof and unfiltered. We asked to Drew to hold for and age to 10 years 2 additional barrels. Last minute, Drew decided we might be interested in an 8 year wheated bourbon. We sampled 4 different barrels. I thought they could use some more age and passed on this one. Others disagreed and the group has purchased 1 barrel.

Drew gave us the full tour. The distillery is a thing of beauty. Drew has the Willett family original recipe and they are distilling using that mashbill. They are making both Bourbon and Rye Whiskey. After tour, Drew grabbed a drill and took a few of us up to the top of one of their rickhouses. The drill is a quick way to grab a sample from a barrel. Drew pulled samples we tasted the KBD distilled bourbon. Just a camera phone picture but thought this one was a good shot. I have been in rickhouses before, but usually they are full. Being on the 5th floor looking down at empty rickhouse and knowing it would soon be full was surreal. This KBD visit was my highlight of this trip.

After spending the morning sampling 10 different barrel proof bourbons and then some straight from the barrel, I’ll admit I went and took a good nap. Without me, the group went on the Heaven Hill (HH). HH makes many bourbons including Evan Williams and Elijah Craig. One member from California has previously purchased barrels from HH and has developed a very good relationship with them. Our group prefers to buy single barrel at barrel proof unfiltered bourbon. HH has always said no to this request in the past. They would only sell something that went into one of their standard offerings. Well, they finally said OK and decided to show off what they could do. They rolled these barrels for tasting:

Bernheim Wheated Bourbon – same product as in Parker’s Heritage Wheated Bourbon

10.6 YO – 126.9PF

11.6 YO – 122.4PF

Rye – DSP 354

3.6 YO – 126.0PF

3.6 YO – 125.6PF

Old Fitzgerald – distilled at Stitzel Weller

20YO – 130.0PF

Bourbon – Prefire HH

22.1 YO – 152.1PF

22.2 YO – 152.3PF

21.2 YO – 129.5PF

Bernheim Wheat – Straight Wheat Whiskey

7.5 YO – 136.0PF

6.2 YO – 130.2PF

Mellow Corn – corn whiskey aged in used barrels

8 YO – 125.5PF

11 YO – 139.7PF

This group did not have prior commitments for purchase at HH, so we are currently polling members to see what we might purchase. While you might get the most excited about the 20YO Stitzel Weller Old Fitz, all said it was too woody. Most thought the Rye was too young. Corn Whiskey, aka legal moonshine, usually is aged very little. The 8YO corn whiskey tasted has received some great reviews.

Late Saturday afternoon, we had a cookout at the GN. One straightbourbon member who works in a restaurant had Allen Brothers donate 32 steaks. A couple of pork butts were also smoked and I made up some Thai Slaw. Several others brought side dishes and desserts. From here, Bob, Allan, and myself went to KY Bourbon Festival Sampler. Most of the distilleries and brands have booths setup where you can get a sample, typically in a logo-ed glass that you get to keep. Jim Rutledge, Master Distiller, at Four Roses was there and we had a nice conversation with him. Then back to the Gazebo. I was designated driver that night, so my participation was very limited. I did sample of Cabin Still at 90 proof from the 70’s that was remarkable.

We started road trip back early Sunday morning. We elected a different route coming home – stopping at casino resort in Biloxi on Sunday night. This route takes us route by a cousin of mine in Hartselle, AL, so able to stop and have a brief visit. Randy & I both won a little money gambling (although him way more than me). The other great thing about this route is it passes by Don’s Specialty Meats outside of Lafayette, LA. I can’t pass on fresh hot cracklin and also stocked up on boudin, crawfish tail meat (from LA – not China), some rabbit sausage and few other items.

Overall, this was the best trip I have been on the KY. Looking forward to next year’s version.